Contra Douay-Rheims Onlyism

A deep dive into Pope Pius XII's papal encyclical on biblical studies.

Note: Reading about the formation of the Western legal tradition led me to reading about the Catholic Church led me to reading the Bible. This newsletter will serve as place for me to share my thoughts as I work my way through the Catholic (and Protestant and Eastern Orthodox and even Jewish) world of Scripture.

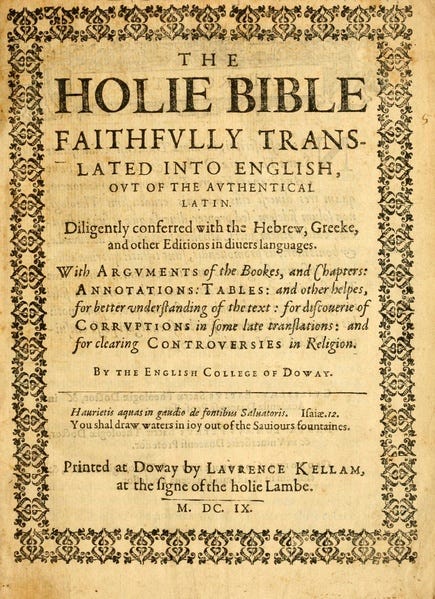

Among traditionalist Catholics, the 17th-century Douay-Rheims translation of the Bible, revised in the mid-18th century by Bishop Richard Challoner (“DRC”), is considered among the best translations available in English, if not the best. Some take it even further than that. Just like those Protestants cwho advocate for only reading the King James Version, some traditionalist Catholics advocate for only reading the DRC.

When I started lurking in trad Cat circles and researching the issue of which Bible translation to read, the DRC was the overwhelming recommendation so I bought it. However, I quickly came to dislike it. Its archaic quality felt wooden to me, not exalted. Somewhere around Exodus or Numbers I put it aside for modern translations.

When I shared my experience on various forums like FishEasters and Facebook, the response was overwhelmingly negative. I was just wrong, darn it, the DRC was either the best or, more frequently, the only Bible worth reading! I had best just get over myself and learn to love it.

But after doing research, like reading some papal encyclicals for myself, I have to disagree. The DRC might be their favorite, but that’s merely a preference. Nothing that I can find in Church doctrine holds that the DRC is the only Bible a traditional Catholic should read. In fact, prior to Vatican II, things were clearly going in a different direction, away from the DRC.

Two important points before I get started:

I’m not arguing that DRC lovers shouldn’t love or read the DRC. If a person prefers it, if that translation brings him closer to God, if it provides spiritual sustenance, terrific, keep doing what you’re doing. My position is merely that DRC Onlyism is incorrect, that other translations are doctrinally valid, worth reading, and that there’s nothing wrong with flat-out ignoring the DRC.

Because I’m arguing from a traditionalist Catholic perspective against a traditionalist Catholic POV, you won’t find me using any substantive evidence or support from modernist popes or resorting to Vatican II justifications. I’m arguing my position solely on trad Cat grounds.

Pro-DRC Onlyism

What’s the trad Cat case for only reading the DRC? There are four main links in their chain of reasoning. This is my attempt to steelman the basic DRC Only position by combining the reasoning used by people such as Marianland, Taylor Marshall, Russ Stutler, and Augustino Taumaturgo. (It should be noted that the latter three aren’t DRC Onlyists, but their basic points are used by DRC Onlyists.)

St. Jerome began the Latin Vulgate tradition in the 4th century.

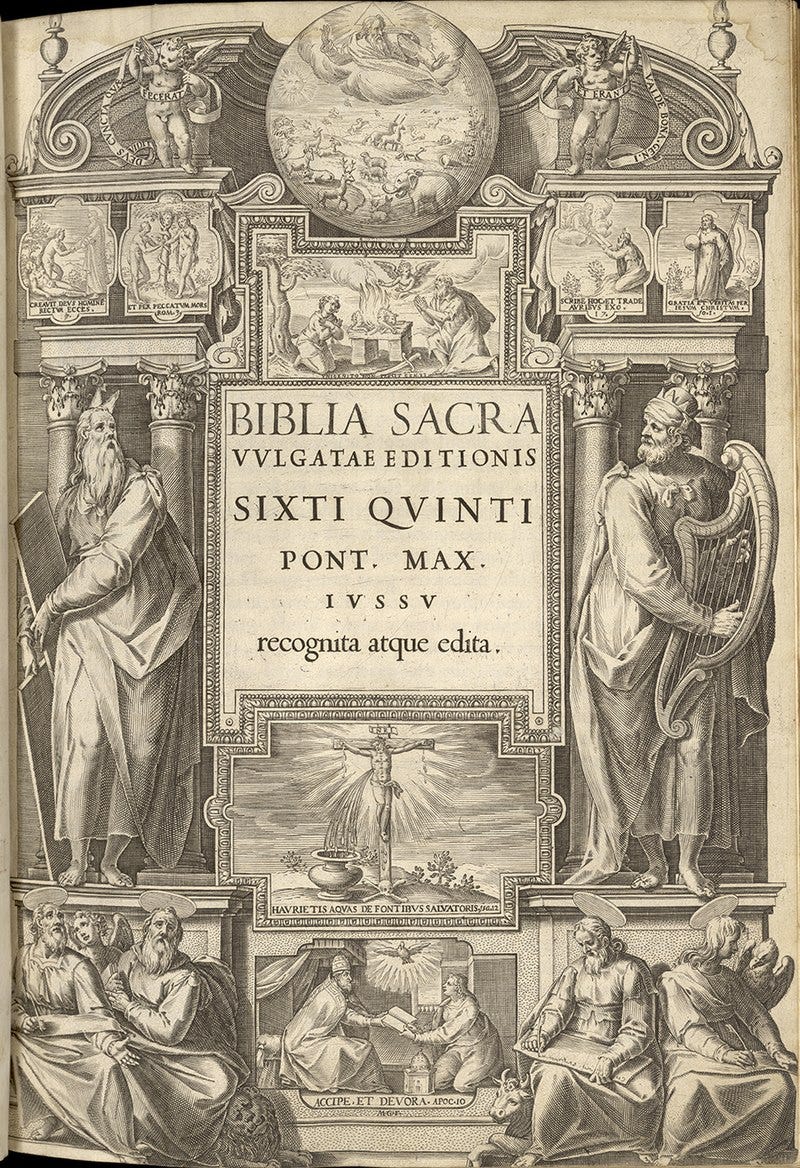

Prior to St. Jerome, Latin translations of the Old Testament were based on the Greek Septuagint. St. Jerome began the practice of using the original Hebrew text as the basis for his translation. Furthermore, St. Jerome translated the OT into Latin from Hebrew manuscripts that are now lost to us. The critical texts that modern translators rely on are part of the Masoretic tradition that started in the 7th century while the most recent full copy of a Masoretic text dates from the 11th century. St. Jerome worked from texts that pre-date the Masoretic tradition, thereby making the LV presumably more reliable. The Clementine Vulgate, published in 1592 and the most recent revision of the Latin Vulgate, is in a tradition that stretches back over 1,000 years. The Clementine Vulgate was the standard Bible in the Roman Catholic Church until 1979.

The Council of Trent declared the Latin Vulgate to be authoritative.

In the Fourth Session of the Council of Trent, in the section titled “Decree Concerning the Edition, and the Use, of the Sacred Books,” the Council held:

Moreover, the same sacred and holy Synod,--considering that no small utility may accrue to the Church of God, if it be made known which out of all the Latin editions, now in circulation, of the sacred books, is to be held as authentic,--ordains and declares, that the said old and vulgate edition, which, by the lengthened usage of so many years, has been approved of in the Church, be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever.

The DRC is a faithful, word-for-word translation of the Latin Vulgate.

Although the formal v. dynamic equivalence framework didn’t exist in the late 16th and early 17th centuries when the English College translated the LV at Douay, it’s undisputed that the DRC follows the “word-for-word” formal equivalence philosophy. The DRC’s English is noted for its “Latinisms.”

In Divino Afflante Spiritu, a papal encyclical published in 1943, Pope Pius XII declared the Latin Vulgate “to be free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals.”

Hey, if a pope — a traditionalist pope, not a modernist one, and one regarded by the hardest of the hardcore as the last valid pope — makes such a definitive statement, doesn’t that end the issue?

Anti-DRC Onlyism

No, I don’t think that ends the issue.

I’m mainly going to analyze Divino Afflante Spiritu (“DAS”) — promulgated on Sept 30th, the Feast of St. Jerome — a document that I’m guessing most people haven’t read. Because while Pius XII indeed said the Vulgate is “free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals,” he said a lot more besides that complicates the DRC Only position.

First, declaring the Vulgate “free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals” is also known as the nihil obstat. Per Canon 823 § 1:

In order to safeguard the integrity of faith and morals, pastors of the Church have the duty and the right to ensure that in writings or in the use of the means of social communication there should be no ill effect on the faith and morals of Christ's faithful. They also have the duty and the right to demand that where writings of the faithful touch upon matters of faith and morals, these be submitted to their judgement. Moreover, they have the duty and the right to condemn writings which harm true faith or good morals.

The nihil obstat can appear not just on bibles, but on any writing touching upon faith and morals. Furthermore, “free of error” doesn’t mean that the book with the nihil obstat is therefore “the best,” it merely means what it says, that it is free of error in that it doesn’t violate Church doctrine. The nihil obstat on my Knox version says, “It is not implied that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contentions, opinions or statements expressed.”

Second, the DAS — along with every other papal encyclical of which I’m aware — says nothing about the DRC translation. Just like the phrase “right to privacy” appears no where in the Constitution, the phrase “Douay-Rheims” appears no where in DAS or any other document promulgated by the Vatican. Notice too how many DRC Onlyist arguments are really about the authority of the Latin Vulgate and they try to sneak in the DRC through the backdoor. They use the transitive law, something like, “The Vulgate is the best, and the DRC is the best/only translation of the Vulgate, therefore the DRC is the best/only.”

Third and most importantly, the substance of DAS, subtitled “On Promoting Biblical Studies,” is about the need to translate the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek texts. Pius XII begins by noting that Pius X himself (the namesake of the SSPX!) recommended “investigations and studies on which might be based a new edition of the Latin version of the Scripture.” (DAS section 9, emphasis mine). The Clementine Vulgate, itself a revision of the Sixtine Vulgate, was due for its own revision. Pius XII recognized that “there is no one who cannot easily perceive that the conditions of biblical studies and their subsidiary sciences have greatly changed within the last fifty years.” (DAS section 11.) Three years before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Pius XII acknowledged that already there were “relevant excavations” providing “information at once more abundant and more accurate” for a “more correct and fuller understanding of the Sacred Books.” (DAS section 11, emphasis mine).

It was time to study the original languages of Hebrew and Greek with recourse to the original texts. (DAS section 14). It would be perverse to ignore them given that “there are now such abundant aids to the study of these languages that the biblical scholar, who by neglecting them would deprive himself of access to the original texts, could in no wise [sic?] escape the stigma of levity and sloth.” (DAS section 15). Lest anyone think there was anything uncatholic about this approach, Pius XII observed that Augustine “put in the first place the care to possess a corrected text” whose “purpose is to insure the sacred text be restored, as perfectly as possible, be purified from the corruptions due to the carelessness of the copyists and be freed, as far as may be done, from glosses and omissions.” (DAS section 17).

But what about the status of the current Vulgate? How does the call for a revision based on the original languages affect the status of the edition that the Church had been using for the past four centuries? Pius XII said it was “historically certain” that the Council of Trent “beg[ged]” the “Sovereign Pontiff in the name of the Council that he should have corrected, as far as possible, first a Latin, then a Greek, and Hebrew edition, which eventually would be published for the benefit of the Holy Church of God.” (DAS section 20). If the Church never followed through, it was due to the “difficulties of the time and other obstacles,” which I think is a polite way of saying the Church had its hands full at the time battling the Reformation. (DAS section 20). While the Vulgate had been in “legitimate use in the Churches throughout so many centuries,” the “authenticity of the Vulgate was not affirmed by the Council particularly for critical reasons.” (DAS section 21). The Vulgate may be “free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals” (the nihil obstat I referred to above), but that authenticity was “juridicial,” not “critical.” (DAS section 21). In other words, the Vulgate derived its authority from its status as the one in use by the Church, not because its authority rested on it being the best critical edition.

Pius XII then argued that the “authority of the Vulgate in matters of doctrine by no means prevents — nay rather today it almost demands — corroboration and confirmation by the original texts” so that the “correct meaning of the Sacred Letters is everywhere daily made more clear and evident.” (DAS section 22, emphasis mine). Of course, when translators and exegetes use the original languages for “discovering and expounding the genuine meaning of the Sacred Books” (DAS section 23) they must “take into account the explanations and declarations of the teaching authority of the Church.” (DAS section 24).

Pius XII hoped that a “deeper and more accurate interpretation of Sacred Scripture” would help clarify “well nigh unintelligible” passages like the “first chapters of Genesis” or the difficulties in translating the Psalms. (DAS section 31). Of course, as Augustine pointed out, “God wished difficulties to be scattered throughout the Sacred Books” so that “we might be urged to read and scrutinize them more intently, and, experiencing in a salutary manner our own limitations, we might be exercised in due submission of mind.” (DAS section 45). But the existence of such complexities doesn’t mean one “should in any way be deterred from grappling again and again with these difficult problems.” (DAS section 46).

Finally, Pius XII calls on everyone to judge the exegetes’ work “not only with equity and justice, but also with the greatest charity; all moreover should abhor the intemperate zeal which imagines that whatever is new should for that very reason be opposed or suspected.” (DAS section 47, emphasis mine). Pius XII knew that any new edition would do what all new editions do — they offend, ruffle feathers, and otherwise upset people who are used to doing things a certain way. Also, these new critical editions should “with the approval of the Ecclesiastical authority” be translated into “modern languages.” (DAS section 51).

To sum up, Pope Pius XII, considered by some to be the last traditionalist pope, called for:

the creation of a new critical edition of the Latin Vulgate based on the original Hebrew and Greek

which is then translated into the vernacular, modern languages

For those wedded to DRC Onlyism, DAS is a little problematic, no?

“But wait,” you say. “It’s all well and good for the last based pope to call for this or declare that. What actually happened? Did the encyclical have any practical effect? Also, you are a schismatic heretic for disliking the DRC, but proceed, if only so I can continue arguing with you.” Great question, love your attitude, I’m glad you asked.

In 1933, in the wake of Pope Pius X’s 1907 call for Benedictine monks to produce a new critical edition of the Latin Vulgate, the Pontifical Abbey of St. Jerome-in-the-City was established. Between 1926 and 1995 the monks produced the Benedictine Vulgate in 18 volumes, comprising the entire Old Testament and deuterocanonical books. But we know after Pius XII there was John XXIII and Vatican II, which produced its own version of the Vulgate, the Nova Vulgata in 1979, so the Benedictine Vulgate was suppressed and the Pontifical Abbey of St. Jerome-in-the-City was disbanded. I bet this book is interesting, but it doesn’t look like it’s been translated into English.

In 1949, Monsignor Ronald Knox published his English translation which was based on the Clementine Vulgate “in light of the Hebrew and Greek Originals.” Knox worked alone for nine years, something rare in the annals of Bible translation, which usually rely on a translation team. Despite being published by Baronius Press, most trad Cats seem to be unaware of the Knox version. Others are put off by its dynamic equivalence, ie it’s too different than what they grew up with. Knox published a short, terrific book on the translation process and the criticism his translation received.

But even despite all of that — despite Pius X creating the Pontifical Abbey of St. Jerome, despite Pius XII calling for a critical Vulgate and vernacular translations, despite the production of the Benedictine Vulgate, despite the Knox translation — English speakers arguably don’t have a formal equivalence translation based on the Latin Vulgate tradition. Within the last 50, 100 years, there are very, very few inherently Catholic translations. The RSV, NRSV, and ESV all derive from the KJV, ie Protestant, tradition. While the KJV has spawned a line of successors, the DRC hasn’t.

If trads love the Vulgate so much, why aren’t they requiring everyone to learn Latin? Why hasn’t there been a movement to revive Latin as, if not a living language, the default liturgical/devotional one? There’s precedent in the Jewish revival of Hebrew. The reason, I think, for the lack of truly Catholic Bible translations and the lack of a Latin revival is the same: Catholics are still overwhelmed by, still dealing with the consequences of, Vatican II. The flashpoint was and continues to be the Traditional Latin Mass. So, just like the Council of Trent never got around to a new critical Vulgate because it was too busy combating heresy, so too contemporary Catholics haven’t gotten around to a new critical Vulgate because they have been busy fighting over the direction of the Church. To speculate further, I think Vatican II is the reason DRC Onlyists exist. The DRC Onlyist sees the Church has under attack and seizes on to tradition like a life preserver. The older, the better. Because the DRC is the oldest, most purely Catholic translation in English, its status has been elevated beyond reason.

Related

Church Latin publishes a great reprint of the Clementine Vulgate. I have one.

I’ve tried the JB, NJB, and RNJB but haven’t warmed up to any of them. The utilitarian editions published by HarperCollins doesn’t help.

I like the NRSV, ESV, and even NKJV far more than the DRC. Yes, I know, they’re at root Protestant, despite the NRSV and ESV having CE editions, but I supplement with a number of other Catholic resources.

The Catholic Bible publishing world lags far, far behind the Protestant one, but that’s a post for another day.